Quality Control: When doing your best is not good enough

written by Maree Stuart

I recently came across a process that went along like this:

- Team completes an activity

- Quality control by review of records and report by a supervisor

- Quality control by review of the records and report by a technical manager

- Quality control by review of the records and report by a committee of technical experts

- Quality control by review of the records and report by a senior manager

- Rejection of initial work performed by the team and the object of the activity.

This process took several weeks and probably countless hours to complete. That adds up.

Can you imagine how demoralizing it would be for the team that kicked off the process, the object of the activity, and for the intervening people whose good work was rejected?

I should add that the process had a preceding step involving evaluation of another organisation through a conformity assessment activity. This was also a costly exercise.

It got me thinking about why we do quality control and when do the costs outweigh the benefits.

What is Quality Control?

Dr Joseph M. Juran explained in his Quality Handbook that “Quality control is a universal managerial process for conducting operations so as to provide stability—to prevent adverse change and to “maintain the status quo.””

Dr Joseph M. Juran explained in his Quality Handbook that “Quality control is a universal managerial process for conducting operations so as to provide stability—to prevent adverse change and to “maintain the status quo.””

He further writes, “To maintain stability, the quality control process evaluates actual performance, compares actual performance to goals, and takes action on the difference.”

We do quality control to ensure we have a predictable and stable process that produces the outcomes we expect.

In a lab, the outcomes are often related to the accuracy and precision of a measurement. How we measure that is through testing materials that have been well-characterised, such as reference materials or standards (accuracy), and showing that when there are variations in the process through different staff, equipment, or time, the process delivers an acceptable degree of variation.

Sometimes, labs can combine their QC activities to provide metrological traceability, say if we were to use a certified standard or reference material. That’s when things get fancy (and sometimes expensive!)

Other quality control measures include the inspection and testing of materials, process intermediaries or outputs. This can range from physical materials through to software, and everything in between.

In a process such as that outlined at the start of this article, it’s a review of records of the process’ performance. That’s a bit like an audit, really.

Is there a limit on how much or how little quality control you should do?

Theoretically, yes. Everything comes at a price.

We know what we’ve been taught by our elders on QC measures. Enduring words like “Do some QC at least once a batch”. Or “Re-run at least one sample once a day”. But have you ever thought about why the QC regime you have in place exists and whether it is the most appropriate?

If you were to think about this- and I know you do, all the time, especially when you have nothing else to think about- you might have realised that your QC program is a perfect risk management tool.

We’ve written previously about risk management and it’s a real risk vs reward story. You could throw caution to the wind and do no QC and then bear the risk that things will go wrong that you don’t learn about until it’s too late. Or you might be more prudent and test everything in triplicate with certified reference materials on either side of each sample. Or, more than likely, you do something in between.

The key is to understand the “why” and “who”. Why is the process being performed? Who has an interest in the performance of the process? That suggests some planning is in order!

Quality Planning

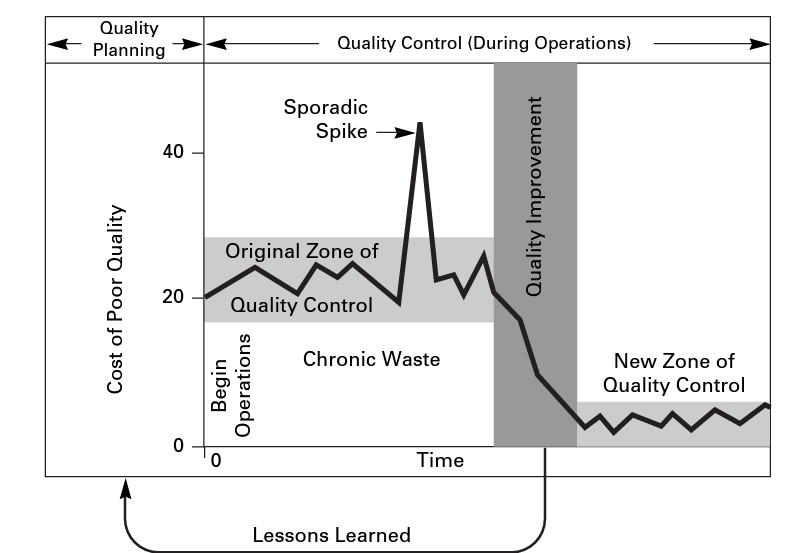

Quality control is one third of Juran’s Quality Trilogy, which links Quality Planning, Control, and Improvement. The diagram below, taken from Juran’s Quality Handbook, shows the link between the components. Errors in the process planning stages lead to chronic waste.

When planning for quality (now called Quality by Design), it’s important to consider the cost of poor quality The American Society for Quality defines this as “the costs associated with providing poor quality products or services.” There are three categories:

- Appraisal costs are costs incurred to determine the degree of conformance to quality requirements.

- Internal failure costs are costs associated with defects found before the customer receives the product or service.

- External failure costs are costs associated with defects found after the customer receives the product or service.

QC falls into the first category.

To remain competitive and sustainable, most businesses want to control costs and maximise revenue. That means that there is only so much a business can spend on appraisal costs. But those costs need to be balanced against the internal and external failure costs. That’s where risk comes into the picture.

If you’re the risk-averse type, who cannot countenance any failure, then that’s when you’ll spend up big on those appraisal costs. And, hopefully, your customers will pay! But what happens if they won’t?

Despite operating in a distorted market, the unnamed organisation with the complicated QC process described at the start of the article does not exist in a bubble. If compliance costs for the market run too high, then people will start to complain. Loudly. No organisation is immune to these pressures, least of all a lab operating in a highly competitive market.

Now, let me come down from my soapbox……

Planning a practical QC regime

It all starts with understanding why you’re performing the work you do and who are the customers and other stakeholders attached to that process. What are their expectations? Are they in a zero–tolerance environment?

WRITE THAT DOWN! And explain it to the people involved in the performance of the process.

Next, work through a risk management process of the activity/ test/ calibration in question.

Next, work through a risk management process of the activity/ test/ calibration in question.

Sometimes lives depend on the outcome of the activity, but not always. Take that into account.

By the end of that, you’ll have an idea of the risk mitigation steps, ie QC activities, that are warranted. Don’t forget that there are costs to any action, and some of these are less tangible and go to morale and staff retention. Does the cost outweigh the benefit?

Next, it’s as easy as evaluating actual performance, comparing actual performance to requirements or goals, and taking action on the difference.

Having created a plan that works and is based on risk, you’ll be in a position to defend your approach to anyone that comes asking. Including your local conformity assessment organisation.

Need help?

That’s why we’re here!

Our Risk Management in the Lab training course will give you all the help you need. We’ll answer your questions and give you practical, hands-on activities to support your work and your business. We can run it in-house so all your people can be risk savvy.

And stay tuned for our new course in Advanced Lab Management and Quality in October! Join our waitlist today by dropping us an email.

Call Maree on 0411 540 709, or email info@masmanagementsystems.com.au and discover how we can support your QC and risk management efforts in your lab!

Remember, you don’t have to do this alone!

People who enjoyed this also read